The Daily Churn

“If we save a few farms, we’ve done a good thing” — MIT graduate

HitchPin app connects buyers and sellers of agricultural goods and services

HitchPin has a twofold mission: save existing farms and help new farmers get a toehold. Similar to how Airbnb got its start amid a collapsed housing market, CEO and founder Trevor McKeeman — a Kansas farm kid turned entrepreneur — says the time is ripe for his new app, which facilitates rapid sales of various agricultural goods and services.

McKeeman compares the current situation in agriculture to that of the 1980s, when a ruinous combination of crushing debt, low commodity prices and government policy forced thousands of families off their farms. Analogously, he says a lot of today’s farmers bought expensive equipment “like $800,000 combines” when commodity prices were high, but a five-year pricing slump has eroded their ability to afford the equipment. This combined with other pressures has resulted in scores of U.S. farm closures, including over 2,700 dairies just in 2018.

“This is the time,” adds the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) graduate, “when producers will actually start looking around and say, ‘I’ve got to change the way I do business or I’m not going to be in business in the future.'”

HitchPin is designed to help farmers reduce their costs and increase revenue, but can how far can one app really go?

HitchPin is designed to help farmers reduce costs and increase revenues.

Time is money

It’s quite simple really. Pointing to a cardboard sign marked “Hay 4 Sale,” McKeeman explains how a lot of farmers might spend half a day calling everyone in their network to buy hay, which is the first thing the app offered. But within two seconds of opening the app on their smartphone, they will know exactly who within a certain radius has some available.

Likewise, if farmer Miguel has a really expensive swather (which cuts hay or other small grain crops and forms them into windrows) and extra time on his hands, he can list the days he is available to help others, along with his pricing per acre. Then, someone in his vicinity will open the app and highlight the field that needs swathing, and the app will automatically calculate both the acreage and cost. Once both parties accept the pending transaction, payment goes into escrow until the goods are produced or services are complete.

“My Dad actually listed his hay,” McKeeman says. “It sold within a couple of days; payment was deposited in his bank account, and he goes: ‘Trevor, I understand what you’re doing with this app. I get it.'”

This isn’t accidental. While building the app over a period of several years starting in 2016, McKeeman and his team visited thousands of farmers to better understand their needs. It’s one thing if you’re building a photo-sharing app and you lose someone’s photo, he says. It’s another thing entirely when you lose a $20,000 transaction that’s a farmer’s livelihood. “We have to be thoughtful about all this.”

Building a world-class tech company in Kansas

As he set out to build “the most sophisticated app in the world for farmers,” naysayers urged him to hit California for the requisite talent and investors. On the contrary, McKeeman found both right there in Manhattan, Kansas where he is based — and they better understand the unique exigencies of agriculture than an urbanite might.

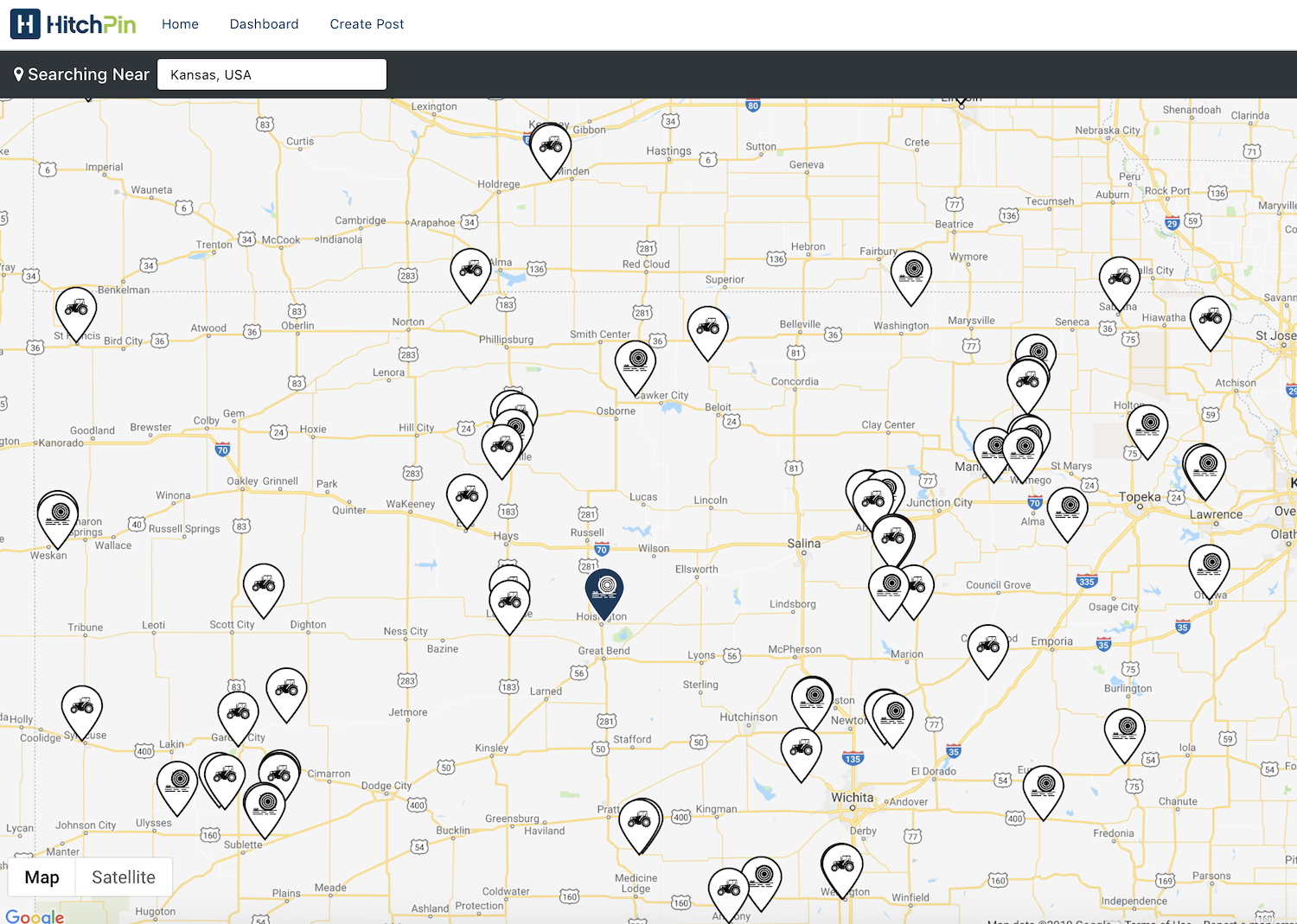

This screenshot illustrates the icons that are visible on HitchPin when users first open it.

One of those investors, Nathan Kells, is a self-proclaimed fifth-generation farm boy in SW Kansas who works with his younger brother Grant. At 45 and 42 respectively, they grow crops on 8,000 acres of land, producing about one-third of the feed they need for their family heifer operation. Kells first met McKeeman in around 2009 when they both participated in the Kansas Agriculture and Rural Leadership (KARL) program. After completing the two-year program, they stayed in touch.

“Then he started talking to me about this agricultural app called HitchPin and laid out the basics of what it was,” says Kells. “I could immediately see the need for it — because I could use something like that myself.”

Driven by that and the desire to learn more about how startups work, he decided to invest. That was about a year ago, he says. Though Kells declined to say specifically how much his family invested, he says it was the largest investment they have made to date. “I definitely believed in the product or we wouldn’t have put money in it.”

What’s next for HitchPin

Today, McKeeman says HitchPin’s 30% growth rate (month-over-month) suggests it has hit a nerve within the agriculture community — and he and his team of around 14 (part-time and full-time employees) are preparing to scale up soon. But it has some way to go before there’s a critical mass of users. Kells says he would love to buy more hay, but “if you look at SW Kansas right now, there’s like one listing for hay.” As for Washington, where The Daily Churn is based, the nearest person offering swathing services is about 2,000-miles away.

“That was intentional,” says McKeeman. “We started here because we knew the area and we knew a lot of the players. But as far as the Pacific Northwest, it’s very much next in line — particularly on the hay side.” He adds that the startup didn’t fully turn on its “marketing engine” until this past summer, and then focused their efforts on the midwest to start.

“We wanted a strong infrastructure in place before we branched out.”

To get a sense of whether there would be interest for the app in Washington, we introduced HitchPin to 35-year-old Dwayne Faber, who runs two dairies in Western Washington.

“This is awesome!” he told us in an email. “This app would be incredibly valuable in connecting buyers and sellers, as well as [give] custom operators the ability to get their rates out there. I’d love to see its adaptation in the PNW.”

Driven by memories of his own parents surviving on pure grit during the 1980s farm crisis — as they made the transition from teaching to growing wheat, soybeans and hay — McKeeman stays close to his original intention of improving the odds for farmers weathering today’s challenges.

“If we save a few farms,” he says, “we’ve done a good thing.”

:: Images courtesy HitchPin